🚀 Hey everyone!

I’ve been working hard on my Heirloomie app, and I finally have a demo you can play with! 😊

This is just a preview, not the full edition — but it gives you a chance to explore how Heirloomie reads documents, organizes memories, and begins shaping family stories.

Try it here:

👉 https://heirloomie-v3-2-storyteller-edition-269673785247.us-west1.run.app

Let me know what you think. It’s still in development, but I’m excited to share this journey with you as Heirloomie grows into a full heritage‑preservation platform.

🌿 A Small Note About Building This App

Creating Heirloomie has been a labor of love — months of designing, testing, refining, and shaping a space where family history can finally feel alive, organized, and meaningful. Every screen, every tool, every hub has been built with the intention of helping families preserve their stories in a way that feels intuitive, beautiful, and lasting.

This demo is just the beginning, a small glimpse into a much larger vision. The full Heritage Edition is still being crafted, but each step brings us closer to a complete platform built to honor the people and memories that made us who we are.

🌿 Heirloomie – Core Feature Highlights

🧬 1. Roots & Branches (Family Tree System)

– Dynamic, interactive family tree

– Add people, relationships, life events, and connections

– Attach documents, stories, and photos to each person

– Automatic consistency checks & duplicate detection

– Profile analysis tools to help clean up messy trees

📜 2. The Workbench & File Cabinet (Document Hub)

– Upload scanned, handwritten, typed, or digital documents

– Highlight text directly inside documents

– Extract important details (names, dates, places)

– Attach documents to:

– People

– Stories

– Facts

– Journals

– Timelines

– Research logs

– Organize files into collections and folders

🕯️ 3. Story Studio (Storytelling & Memory Preservation)

– Create rich, narrative stories about ancestors

– Build timelines, life summaries, and memory pages

– Add photos, documents, and quotes

– Turn raw information into meaningful family stories

– Save stories to individuals or entire branches

🔍 4. Discovery & Context Tools

– Interpret old records

– Identify key facts inside documents

– Provide historical context for events, places, and eras

– Help users understand the meaning behind what they find

🧠 5. Ancestria (Your In‑App Guide)

– Helps navigate the app

– Assists with research tasks

– Interprets documents

– Supports story creation

– Answers questions about your tree and entries

🧬 6. DNA Hub

– Organize DNA matches

– Track shared segments

– Connect DNA results to family tree profiles

– Build hypotheses and relationship theories

🌳 7. The Grove (Memorial & Tribute Space)

– Create memorial pages for loved ones

– Add photos, stories, and life highlights

– Share with family members

– Preserve legacies in a sacred, respectful space

🗂️ 8. Planner & Organization Tools

– To‑do lists

– Research tasks

– Project planning

– Reminders

– Checklists for genealogy work

📚 9. Master Research Log

– Track every document, source, and discovery

– Keep notes, citations, and research steps

– Organize by person, family, or project

– Maintain a clean, professional research trail

🎤 10. Voice Mode (Hands‑Free Interaction)

– Navigate the app using voice

– Dictate notes, stories, or journal entries

– Designed for accessibility and ease of use

🖥️ 11. Accessibility & Elder‑Friendly Design

– Large text options

– High‑contrast mode

– Voice‑first navigation

– Simple, intuitive layout

– Designed for all ages and abilities

🌿 Heirloomie – Full Hub Overview (Storyteller Edition)

A deeper look at everything inside the current build.

1. Dashboard

Widgets include: Heritage Streak, Active Project, Planner Overview, Recent Uploads, Ancestral Vitality, Daily Inspiration, On This Day, Ancestor Spotlight, Recent Activity.

2. Ancestria

Voice Mode and Chat Interface for guided navigation and support.

3. Thread Lines

Collaborative message boards organized by family tree.

4. Roots & Branches (People Hub)

Browse:

– Interactive Tree (Horizontal, Vertical, Radial)

– Fan Chart

– Pedigree View

– Descendant View

– Person Directory

– Kinship Report

Analyze:

– Relationship Calculator

– Compare Profiles

– Consistency Check

– Tree Statistics

Manage:

– Tree settings and lists

5. Research Assistant (Tools Hub)

Dashboard, Research Guides, and tools including:

– Record Search

– Fact Finder

– Record Helper

– Research Opportunities

– Source Critic

– Data Explorer

– Recipe Rescuer

– Audio Transcriber

– Notes & Records

– Legacy Contact

– Family Trivia

6. File Cabinet

Folder management + Universal Document Processor (transcription, translation, data extraction).

7. Planner & Journal

Calendar, Kanban tasks, journal, research trips, expenses, address book, master log, and toolbox (Date Calculator, Soundex, Roman Numerals).

8. Story Studio

All Stories, Recipe Box, Folders, and Editor Tools (Drafts, Story Arc Analysis, Read Aloud).

9. Media Hub

All Media, Unassigned items, and Albums.

10. The Grove

Memorials and Cemetery Directory.

11. Places

Ancestor Atlas, migration paths, and place‑name standardization.

12. Timeline

Contextual timelines, person comparisons, and Time Machine historical reports.

13. DNA Hub

Dashboard, Match List, Groups, Cluster Matrix, Relationship Chart, Chromosome Browser, Ethnicity Estimate.

14. Loom Classes

Lessons (Beginner–Advanced), Certifications, Welcome Toolkit, Teacher’s Lounge, User Manual.

15. Tags

Global tag groups for organizing everything across the system.

Tag: Coni

🪶 Barkhamsted Light House Village: A True American Story

I have decided to write a children’s book—because some stories are too important to wait until we’re grown to hear them. This one has lived in my heart for years, passed down through generations, whispered in family stories, and rooted in the soil of a forgotten village that shaped who I am.

Now FREE to Read Online—Because This History Belongs to All of Us.

Some stories are too important to keep behind closed doors.

Barkhamsted Light House Village: A True American Story is one of those stories—a legacy of resilience, erasure, and reclamation that shaped my family, and echoes through the roots of this country.

That’s why I’ve made the full book available to read online, free of charge. Because this isn’t just my history. It’s ours.

🌿 What Is the Barkhamsted Light House Village?

Hidden deep in the woods of Connecticut, the Barkhamsted Light House Village was home to a multiracial, multicultural community of Native, African, and European descent.

These families—Chagum (Chaugum/Chaugham), Barber, Freeman, Wilson, and others—lived together in defiance of the rigid racial and social boundaries of their time.

They were labeled “outcasts.” But they were builders, farmers, protectors, and storytellers. They were my ancestors.

📖 Why I Wrote This Book

As a genealogist and historical researcher, I’ve spent decades tracing the truth of my lineage. What I found in the Light House Village wasn’t just a forgotten settlement—it was a foundation. A place where dignity, identity, and community thrived despite systemic erasure. But their story had been distorted, dismissed, or buried.

So I wrote this book to set the record straight—not just for my family, but for every family whose truth has been silenced.This is a true American story. And it deserves to be known.

💻 Read It Now, Share It Freely

You can read the full book online, right now, for free:

Whether you’re a descendant, a history lover, or someone seeking deeper understanding of America’s hidden past, I invite you to explore this story—and share it. Because healing begins with truth. And truth belongs to everyone.

🔍 What You’ll Discover – Meticulous research drawn from land deeds, court records, oral traditions, and archaeology – Personal reflections on legacy, identity, and reclamation – Illustrations that bring the village to life – A call to action to honor erased histories and uplift living descendants.

💔 Why It Still Matters

In a time when history is contested and truth is politicized, this story reminds us: the past is not gone. It lives in us. And we have a responsibility to carry it forward with clarity, compassion, and courage.

The Barkhamsted Light House Village may have been erased from maps—but not from memory. And now, through this book, it stands again.

🌿 In honor of those who came before, and for those still finding their way— To my ancestors: I see you.

📌 A Note About Access

At this time, Barkhamsted Light House Village: A True American Story is available to read online only. I haven’t yet figured out how to make personal copies available for purchase—and truthfully, this isn’t about money for me. It’s about truth. Legacy. And love.

I wrote this book to honor my ancestors and share their story freely with anyone who needs it. When the time comes to offer printed copies, I’ll make sure they’re accessible to all. Until then, I invite you to read, reflect, and share the online version with anyone who might find healing or connection in its pages.

Thank you for walking this journey with me.

🪶 Coni Dubois

Descendant of the Light House Village – Keeper of Stories

Genealogist • Author • Legacy Advocate

Interested in checking out my YouTube channel? I’d love for you to take a look!

To view:

As I prepare for the Barkhamsted Lighthouse Gathering, which marks its 10th year since its inception, I am also revamping and modernizing my various social media channels. My goal is to streamline all of my content and make it easily accessible. Additionally, I am working on creating new research materials for the upcoming occasion.

With that said, I have tons to share and more stories to tell and looking forward to catching up with everyone.

🤗 Coni

🍂 Happy Thanksgiving from Jay, Coni & Dubois Family

In gratitude’s embrace, we gather near,

Jay and Coni, hearts filled with cheer.

On this Thanksgiving, our voices rise,

A wish to share beneath autumn skies.

May blessings shower upon far and wide,

Where love and kindness forever reside.

Let families unite, old and anew,

Embracing memories, both old and true.

On this day of gratitude, let laughter fill the air,

May joy and harmony be found everywhere.

May tables be laden with food so divine,

And cherished memories forever entwined.

Let kindness be our language, compassion our song,

As we lift each other up, together we belong.

May friendships flourish, like autumn’s golden hue,

And gratitude be the light that shines through.

May families be embraced, both near and far,

As we cherish the bonds that truly are,

May homes be filled with warmth and delight,

And gratitude be our guiding light.

In this season of thanks, our hearts overflow,

With love and appreciation, our wishes we bestow.

May blessings be abundant, each and every day,

As we give thanks in our own special way.

Jay and Coni’s Thanksgiving wish, sincere and true,

Is for happiness and blessings to follow you.

May these blessings abound, forevermore,

Enriching our lives, to the very core.

Unlocking the Secrets of Our Ancestors: Harnessing Determination, Courage, and Resilience for Achieving the Impossible

Our ancestors, although long gone, remain as a source of inspiration and knowledge to us. They have left us with a rich cultural heritage that has shaped who we are today. Through their accomplishments, they have taught us the importance of perseverance, hard work, and resilience.

By studying our ancestors, we can expand our knowledge and gain insight into our past. We can learn about the values, traditions, and lifestyles of those who have come before us. Exploring our family roots can help us connect with our heritage and see the world through their eyes.

To gain a greater understanding of our ancestors’ lives, we can search for family records, study historical documents, and even visit family gravesites. We can also research the places our ancestors lived and learn more about the cultures of our ancestors’ times. This can give us a better understanding of how our ancestors interacted with the world around them.

The achievements of our ancestors can give us a sense of purpose and pride. Our ancestors faced many challenges and difficulties, and it is incredible to think of how they were able to overcome the obstacles they faced throughout their lives. Knowing that our ancestors experienced success and triumphs can inspire us to reach further and push the boundaries of what we believe to be possible.

Our ancestors have left us with a legacy of determination, courage, and resilience. By looking to our past, we can find strength and wisdom to help us reach for our goals and achieve the impossible.

“Uncovering My Story: How I Found Meaning in Genealogy Research”

The sentimental journey of genealogy research has been a passion of mine for several years now. For me, every discovery made is like a puzzle piece that slowly begins to reveal an amazing picture of my family’s past. I feel privileged to be the keeper of the knowledge and stories that I’ve unearthed through my research.

I believe that, for many, genealogy research is more than simply finding names on a page. It’s also about bringing our ancestors’ histories to the surface, uncovering the places that define our family roots, and piecing together clues for tracking our lineage. It’s about giving the people from the past an identity all their own, and connecting us to the generations going back further in time.

I find it truly incredible that I can use online databases and software technology to help me in my search. With access to an array of resources, including census records, death certificates, birth records, newspaper archives, military records, and much more, I’m able to dig up information that’s personalized to my family’s history. It’s been an incredible journey so far, and I treasure the new perspectives I’ve gained from my research.

The journey of genealogy research has become a part of who I am. I feel an overwhelming sense of pride when I discover something new about my ancestors, and I can’t help but marvel at how their stories have become mine. I view it as a special responsibility to tell their stories and preserve the facts about their lives.

Genealogy research means more than just gathering data to me. It’s about connecting with my ancestors, understanding the journeys they took, and respecting their place in the timeline of history. It’s about the emotional connection I have to the process and the pride I feel when I uncover new pieces of my family’s past. That’s what genealogy research means to me.

Coni

Tribes of Farmington Connecticut

Connecticut was home to several Native American tribes, including the Mohegan, Pequot, Nipmuc, and Eastern Woodland Indians. The Mohegan and Pequot were the two most powerful and largest tribes. They were both part of the Algonquian-speaking tribes, and their populations were estimated at 2,000 and 8,000 people respectively. The Nipmuc tribe was a smaller group that often merged with other tribes. The Eastern Woodland Indians were more nomadic and spread throughout much of the eastern United States. These tribes had a rich culture and believed in the power of nature and spirituality. Today, these tribes continue to preserve their culture and heritage through museums and cultural centers.

The indigenous people of North America inhabited the Eastern Woodlands, a cultural area that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean through to the eastern Great Plains and from the Great Lakes region to the Gulf of Mexico, covering the present-day Eastern United States and Canada. The Plains Indian culture area is located to the west, and the Subarctic area lies to the north.

Indigenous groups in the Eastern Woodlands spoke various languages belonging to several language groups, including Algonquian, Iroquoian, Muskogean, and Siouan. They also spoke isolated languages such as Calusa, Chitimacha, Natchez, Timucua, Tunica, and Yuchi. Many of these languages remain in use today.

The origin of Farmington lies in the fertile meadows beside the Farmington River that Native Americans referred to as Tunxis Sepus (“at the bend of the little river”). The Tunxis Indians, a sub-tribe of the Saukiogs, built a temporary settlement on these meadows where they fished, farmed, and hunted during the harvest seasons.

Farmington is situated in Hartford County, and its eastern boundary is marked by the Talcott Mountain ridgeline. The Tunxis Indians named the region Tunxis Sepus, meaning “bend of the little river,” which eventually became known as Farmington after its incorporation in 1645. In the 1800s, Farmington gained a reputation as the “Grand Central Station” of Connecticut’s Underground Railroad.

The Farmington River Valley, which includes the area of present-day Farmington, Connecticut, was home to various indigenous peoples for thousands of years before the arrival of European settlers. The primary group of indigenous people who lived in the region was the Tunxis tribe. In the 17th century, European colonists established settlements in the area, leading to conflicts between the indigenous peoples and the settlers. The Tunxis people were eventually forced to abandon their ancestral lands and move to reservations in other parts of Connecticut, while others assimilated into the colonial society.

Today, the Indian tribes and their descendants continue to be an important presence in Connecticut, and their culture and traditions are celebrated and preserved through various cultural heritage organizations and events.

The early Connecticut Tribes were led by several chiefs throughout its history. The information that survives regarding the chiefs of the Indian people is, unfortunately, limited.

Some of the known Tribes include:

The Tunxis tribe, also known as the “Koasek,” lived in central Connecticut and western Massachusetts. They had close relationships with the tribes around them, including the Massachusett, Mohawk, and Mohegan. They primarily lived in villages along the river, which are now part of the towns of Farmington, Avon, and Simsbury.

- The Wangunk, an Algonquian-speaking Native American group, once occupied the region and settlement of Mattabesset alongside the Connecticut River. It is worth noting that the Mattabesset River flows into the Connecticut River near Middletown, Connecticut. European colonial settlers established and developed Middletown on the western part of the region, while a series of settlements emerged on the eastern side, including Chatham and Middle Haddam, which eventually became East Hampton, Connecticut. The Wangunk people were the original inhabitants of the region, and Dutch Europeans first visited the area in 1614. When English colonizers arrived in the area, the Native American sachem, Sowheag (also known as Sequin), led the local community. Following conflicts with the new settlers, Sowheag relocated from Pyquaug – which was later named Weathersfield – to Mattabesett.

- Great Sachem of the Mattabessett Indian Tribe, Sequasson Sequin Sowheag, was born in 1530 in Livingston, New York, USA. His parents were Mattabesetts Seguin Montauk and Sarah Phinney Root. Sowheag later married Sowheag Sequassan “Sequin” Mattabesetts-Wyandance in 1542 in Wethersfield, Hartford, Connecticut, USA. Together, they had at least two sons. Sowheag passed away between 1605 and 1635 in Montauk, Suffolk, New York, USA, at a remarkable age of 105 years old. There are varying spellings for Mattabesset, such as Mattabesec, Mattabeseck, Mattabesset, Mattabesset, and Mattabéeset. Despite this, it is commonly pronounced as “Matta-bess-ic.”

- The Pequot and Mohegan tribes were believed to have migrated from the direction of the Hudson River. At the time of initial contact with Whites, the Pequots were viewed as warlike and feared by neighboring tribes. The Pequot and the Mohegan were jointly ruled by Sassacus until the revolt of Uncas, the Mohegan chief. In 1635, the Narraganset drove the Pequot from a corner of present-day Rhode Island that they had been occupying. Two years later, the murder of a trader who had mistreated some Indians embroiled the Pequot in war with the Whites. At the time, their leader controlled 26 subordinate chiefs and claimed authority over all of Connecticut lying to the east of the Connecticut River and as far west as New Haven or Guilford, as well as all of Long Island except the westernmost end. Through the intervention of Roger Williams, the English secured the help or neutrality of surrounding tribes. The English then attacked and demolished the principal Pequot fort near Mystic River, killing over 600 people of all ages and genders. The tribe was so weakened that after several desperate attempts at further resistance, they split into small groups and abandoned their homeland in 1637. Sassacus and many of his followers were intercepted as they attempted to flee to Mohawk, with most of them either captured or killed. Those who surrendered were divided among the Mohegan, Narraganset, and Niantic tribes, and their land came under the control of Uncas. Although their Indian overlords treated them harshly, the Pequots were eventually taken out of their hands by colonists in 1655 and relocated to two villages near Mystic River, where some of their descendants still reside. Some individuals relocated to other places such as Long Island, New Haven, and the Nipmuc country, while others were kept as slaves among English settlers in New England or sent to the West Indies.

- The Pequot Indians, also known as Sickenames in a Dutch deed mentioned by Ruttenber (1872), meant “destroyers” according to Trumbull’s (1818) translation. The Pequot tribe belonged to the Algonquian linguistic stock and spoke a y-dialect that was closely related to Mohegan. The Pequot tribe held the coastal area of New London County from the Niantic River to nearly the Rhode Island state border. Before being forced to leave by the Narraganset, the Pequot extended into Rhode Island up to the Wecapaug River.

The Pequot tribe had a range of settlements: Asupsuck, which positioned inland from the town of Stonington; Aukumbumsk or Awcumbuck, located near Gales Ferry in the center of the Pequot territory; Aushpook, situated in Stonington; Cosattuck, presumably close to Stonington; Cuppanaugunnit, likely located in New London County; Mangunckakuck, probably positioned below Mohegan along the Thames River; Maushantuxet, located in Ledyard; Mystic, near West Mystic on the west side of the Mystic River; Monhunganuck, situated near Beach Pond in Voluntown; Nameaug, near New London; Noank, found at the present-day site of that name; Oneco, located in the town of Sterling; Paupattokshick, positioned on the lower stretch of the Thames River; Pawcatuck, probably near the Pawcatuck River in Washington County, Rhode Island; Pequotauk, located near New London; Poquonock, found inland from Poquonock Bridge; Sauquonckackock, situated below Mohegan on the west side of the Thames River; Shenecosset, located near Midway in the town of Groton; Tatuppequauog, located below Mohegan along the Thames River; Weinshauks, situated in Groton; and Wequetequock, positioned on the east bank of the river of the same name. Mooney (1928) estimated the Pequot tribe had a population of 2,200 in 1600. Following the Pequot War in 1637, the population was reported to be 1,950, but this figure is likely too high. By 1674, the remaining Pequots in their native territory numbered around 1,500, which dwindled to just 140 in 1762. In 1832, only 40 mixed-blooded individuals were reported, but the census of 1910 recorded 66 individuals, 49 of whom resided in Connecticut and 17 in Massachusetts. The Pequots are most renowned for their bitter and catastrophic experience during the Pequot War, as described above. A post village in Crow Wing County, Minnesota bears their name. - The Mohegan tribe is believed to have originated as a branch of the Mahican people. Under the leadership of Sassacus, who was the chief of the Pequot, they were initially subject to Pequot rule. However, they broke away from the Pequot and became independent. After the Pequot tribe was defeated in 1637, Uncas, the Mohegan chief, became the leader of the remaining Pequot and expanded his territory beyond his original borders. Following King Philip’s War, the Mohegan became the only significant tribe left in southern New England. However, as White settlements grew, the tribe dwindled in both size and territory. Many Mohegan people joined the Scaticook, and in 1788, even more, merged with the Brotherton in New York, forming the largest single group in the new settlement. Those who remained stayed in their original town of Mohegan, where a small group of mixed-blood tribe members still exists today.

- The Wawyachtonoc tribe of the Mahican Confederacy occupied the northwestern corner of Litchfield County, but their primary territories were in Columbia and Dutchess Counties, New York. The Mohegan tribe, which means “wolf,” should not be mistaken for the Mahican. The Mohegan people, who spoke a y-dialect closely related to the Pequot, were part of the Algonquian linguistic stock. Initially, the Mohegan inhabited most of the upper Thames Valley and its branches, and later they claimed control over some of the Nipmuc and Connecticut River tribes, as well as the old Pequot territory. The Mohegan had several villages, such as Ashowat, Catantaquck, Checapscaddock, Kitemaug, Mamaquaog, Mashantackack, Massapeag, Mohegan, Moosup, and Nawhesetuck, also several villages including Pachaug, situated in Griswold; Paugwonk, located near Gardiner Lake in Salem; Pautexet, situated near present-day Jewett City in Griswold; Pigscomsuck, found on the right bank of Quinebaug River near the current border between New London and Windham Counties; Poquechanneeg, located near Lebanon; Poquetanock, situated near Trading Cove in Preston; Shantuck, situated on the west side of the Thames River, just north of Mohegan; Showtucket or Shetucket, found close to Lisbon, in the fork of the Shetucket and Quinebaug Rivers; Wauregan, located on the east side of Quinebaug River in Plainfield; Willimantic, situated on the site of the present city of Willimantic, and Yantic, located at the present Yantic on Yantic River.

- Wappinger Indians. The valley of the Connecticut River was the home of several bands which might be called Mattabesec after the name of the most important of them, and this in turn was a part of the Wappinger.

- The Western Niantic Indians resided along the seacoast from Niantic Bay to the Connecticut River. The Western Niantic tribe had two known villages – Niantic or Nantucket, located close to present-day Niantic, and another village near Old Lyme. Originally considered part of the same tribe as the Eastern Niantic, the Western Niantic were separated from them by the Pequot. They suffered significant losses in the Pequot War and, following its conclusion in 1637, were made subject to Mohegan authority. Many Western Niantic people later joined the Brotherton Indians in 1788. While a small Niantic village near Danbury was reported in 1809, it may have contained members from western Connecticut tribes. Nevertheless, Speck (1928) found multiple individuals of mixed Niantic-Mohegan ancestry living among the descendants of the Mohegan tribe. These individuals were the descendants of a pure-blooded Niantic woman from the mouth of the Niantic River. The Western Niantic tribe had an estimated population of 600 in 1600, 100 in 1638, and around 85 in 1761. The name of the Western Niantic is commemorated in Niantic village, Niantic River, and Niantic Bay in New London County. Niantic is also the name of post villages in Macon County, Ill., and Montgomery County, Pa.

- The Algonquian town of Farmington, CT was initially inhabited by the Tunxis tribe before European contact. Sadly, the tribe was devastated by disease and violence, leaving only 50 members alive by 1725. However, in the mid-18th century, members of the Quinnipiac, Sukiaugk, and Wangunck tribes joined the survivors, forming a new group known as the Farmington Indians. Farmington Indians were predominantly Christian, having been introduced to the religion by Rev. Samuel Whitman in 1732. After he died in 1751, Rev. Timothy Pitkin continued the mission, though not as intensely as his predecessor. Nonetheless, the Farmington Indians catered to their own religious needs. Along with six other Algonquian settlements that eventually joined the Brothertown movement also, Farmington became an active participant in regional networks of Algonquian Christian worship.

- The Brothertown movement was a combined tribe created from Algonquian people found around the Long Island Sound. They immigrated to Oneida territory twice: first in 1775 and then again in 1783. Samson Occom preached in Farmington, and in 1772, he introduced his future son-in-law, Joseph Johnson, as a schoolteacher and preacher. Although Johnson’s formal teaching stint there was brief (only ten weeks), he used Farmington as his base from which to organize the Brothertown movement. The Farmington aided and supported Johnson’s cause, proving instrumental to his mission. Most of the immigrants on the unsuccessful 1775 expedition were from the Farmington Indians. These immigrants eventually found refuge in Stockbridge, MA, where some Tunxis were already residing. Years later, when Brothertown was re-established in 1783, Elijah Wampy, a leader from Farmington, joined and became part of the town’s leadership. However, not all Farmington Indians left for Brothertown; some chose to remain in their hometown. Nevertheless, by the end of the 19th century, these remaining Farmington Indians either left the area, died out, or assimilated into a different community.

- During the 18th and early 19th centuries, James Chaugham (also known as Chagum) was one such revered leader, belonging to the Barkhamsted Lighthouse Village alongside his wife Molly (or Mary) Barber. The names Chagum, Chagam, Chaugham, and Shawgum were linked to various Native American tribes in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Block Island. Chaugham’s leadership was vital, negotiating with colonial authorities and preserving his people’s autonomy amidst growing European influence. He was widely respected as a sagacious, sympathetic leader who fervently advocated for his people’s traditions’ protection and preservation. The historical narrative of the Chagum, Chagam, Chaugham, and Shawgum Indians throughout American history is intricate and multifaceted. Several individuals with these surnames were integral participants in early American history, with relations to both European colonizers and other Native American tribes. Moreover, some of them were chiefs or leaders within their respective tribes and played significant roles in diplomacy and decision-making

- Today, many individuals with these surnames are tracing their roots and learning more about their ancestors and their contributions to early American history. It is through the work of genealogists like Coni Dubois that the stories of these tribes and their people are preserved and shared with future generations.

-

- Information on Chagum connections:

- Several different types of historical documents and records mention the Chagum, Chagam, Chaugham, and Shawgum surnames with Native American tribes and individuals. Some of these documents include:

- Treaty records: Many treaties between Native American tribes and European colonizers or the American government include the signatures or names of individuals with these surnames.

- Land records: Several land records in New England and other parts of the United States contain the names of Chagum, Chagam, Chaugham, and Shawgum individuals with land ownership or disputes.

- Census records: Federal census records from the 1800s onwards often include information about individuals’ races or ethnicities, and many individuals with these surnames appear in these records.

- Church records: Many Native American tribes were Christianized by missionaries, and church records from this period often include information about Native American congregants, including their surnames.

- Family records: Many families with these surnames have kept records of their genealogy, including birth and marriage certificates, family bibles, and other documents.

These are just a few examples of the types of historical documents and records that have information about the Chagum, Chagam, Chaugham, and Shawgum surnames concerning Native American tribes and individuals.

- The Barkhamsted Lighthouse was a historical community located in what is now Peoples State Forest in Barkhamsted, Connecticut. Set on a terrace above the eastern bank of the West Branch Farmington River, it was in the 18th and 19th centuries a small village of economically marginalized mixed Native American, African American, and white residents. It was given the name “lighthouse” because its lights acted as a beacon marking the north-south stage road that paralleled the river. The archaeological remains of the village site were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991 as Lighthouse Archeological Site.

- Today, Chief James Chagum/Chaugham is remembered as an important historical figure in Connecticut. Chief James Chagum/Chaugham was also a big part of the Satan Kingdom story. Satan Kingdom is a valley located in Farmington, Connecticut, USA. The origins of the name are not exactly clear but the name Satan Kingdom has been used since the 18th century and has a long history of Native American connections associated with it. Today, the valley is primarily used as a recreational area that offers a range of outdoor activities. It’s home to the Farmington River Tubing, which provides an exciting tubing experience in the river.

- The Satan Kingdom State Recreation Area is also located in the valley and features hiking trails, fishing spots, and picnic areas. Overall, despite the ominous name, Satan Kingdom & Barkhamsted is a beautiful place to enjoy nature and outdoor activities.

- Another location associated with Chagum’s is Chagum Pond, also known as Spring Pond, which is a freshwater pond located on Block Island off the coast of Rhode Island. The pond is named after the Chagum family, which was a prominent Native American family on the island during the 17th century. The Chagum family was part of the Manissean tribe, also known as the Island Indians, who inhabited Block Island before the arrival of European settlers. They were respected leaders among their people and worked to maintain good relations with the English colonizers who were expanding into the region. During the 1660s, tensions rose between the Manisseans and the colonizers over control of the island’s resources. Nevertheless, the Chagum family managed to maintain their position of influence on the island and continued to shape Block Island’s history for many generations. Today, Chagum Pond remains an important natural landmark on Block Island. The Chagum family is recognized as a significant part of the island’s indigenous history.

-

- Today, many individuals with these surnames are tracing their roots and learning more about their ancestors and their contributions to early American history. It is through the work of genealogists like Coni Dubois that the stories of these tribes and their people are preserved and shared with future generations.

I am excited to welcome Ken Feder as one of our new Authors!

Please help me welcome Ken Feder (Kenneth L. “Kenny” Feder), a professor of archaeology at Central Connecticut State University and author of several books on archaeology and criticism of pseudoarchaeology such as Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. His book Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum was published in 2010. His book Ancient America: Fifty Archaeological Sites to See for Yourself was published in 2017. He is the founder and director of the Farmington River Archaeological Project and is the main Archaeologist of our Barkhamsted Lighthouse site!

I am so excited to have him on board and can’t wait to see what he publishes for us!

I will be becoming more active on this blog myself and have tons of exciting things coming souon!

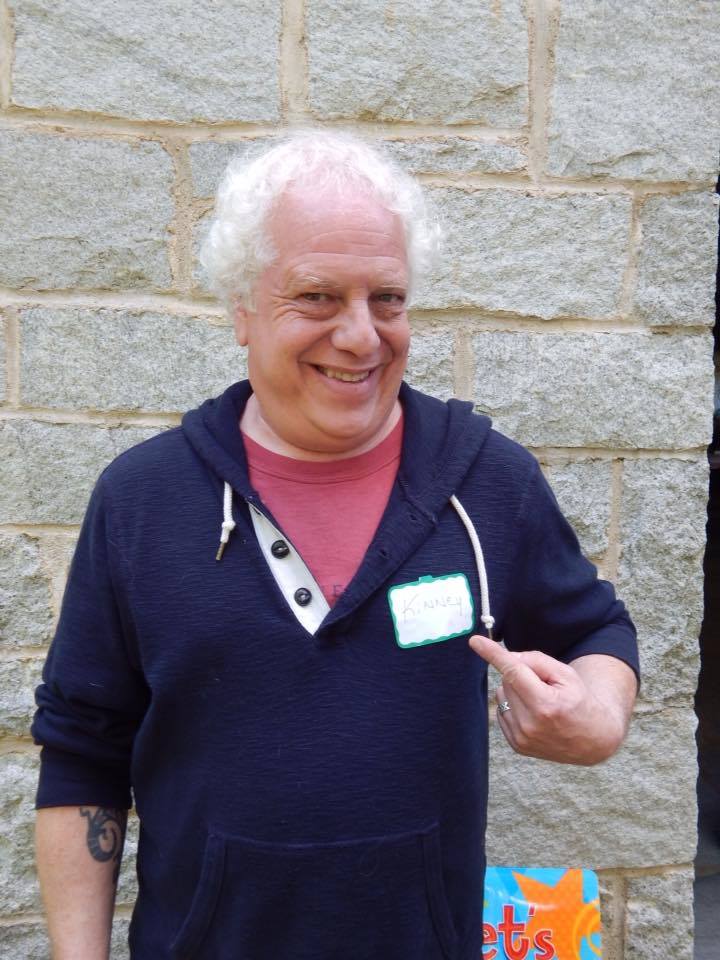

WELCOME KINNEY!!! 😁

“Ever Widening Circle” Research by Coni Dubois is NOW officially open 😁

Disclaimer: This research business provides consulting services to people who desire to obtain data about specific Ancestors/genealogy lines. The research consultant (Coni Dubois) gathers information from credible sources and provides an analysis of her findings & also interpret the information for clients.

coni@conidubois.com

conidubois.com

What family means to me…

My love for my family is my whole being – every ounce of me… loves every ounce of each of you~

I can’t believe I will be 55 this year.

In short… my life has been a very hard one.

Being a strong-wheeled woman I have had to fight my whole life and in turn, I have some family members to this day who can’t stand me. But that’s ok~ They truly never got to know me, or tried to understand me. We all have those people in our lives…If only they would see…family is everything to me~

THIS post though is for my family & friends that chose to love and care for me, truly…thank you from the bottom of my ❤️ know I love you and will always be here for you – as you have been for me~

In all the bad that happened throughout my life, you all have stepped in to be there to hold me up and to push me forward~

I am truly blessed to have all of you in my life.

You have been my rock…my solid ground…my saving grace~ You are deeply loved by me~

Families have their fights, their sadness & their pain.

But it always has its joys, it’s happiness & it’s wonderful moments~ Family is tied by blood and love… and no matter what happens family should always surround those in need and protect those that need us~

I have spent my life searching for family… And have truly been blessed to find so many cousins and family in my life’s journey. You truly amaze me with all your support throughout my time on this earth. Your amazing love is shown to me daily – I am called, texted, emailed, messaged.. in some form, reminded daily at how many truly love me~

I am humbled by each of you~

PLEASE find forgiveness for those who are nillynallys in your life, move past the hatred and the fighting. We have lost so many family members…life is too short, and we need to find love for one another, and get pasted this separation of family. We truly need to bond together to face this unknown world we have ahead of us… I truly worry for our descendants at the world we are leaving them~

I have found my calling…I was meant to be my family Historian/Researcher/Genealogist. I feel I must record all I can on our ancestors….before it is lost~

This is my purpose in life~

It is my legacy… bound by my love for family~

I will be doing it till the day I die~

Coni Dubois